Young, in love and in danger

Teen domestic violence and abuse in Tasmania

Research Brief

Dr Carmel Hobbs

November 2022

Content warning

This research brief contains descriptions and direct quotes of participants referring to experiences (e.g. of violence, abuse and suicide) that may be triggering to readers.

The services listed below can be contacted for support:

- 1800 RESPECT: 1800 737 732

- Full Stop Australia: 1800 943 539

- Rainbow Sexual, Domestic and Family Violence Helpline: 1800 497 212

- Family Violence Counselling Support Service (Tasmania): 1800 608 122

- Blue Knot (childhood and complex trauma support): 1300 657 380

- Well Mob

- 13YARN for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: 13 92 76

- A Tasmanian Lifeline: 1800 984 434

- Lifeline: 13 11 14

- Kids Helpline: 1800 55 1800

- Men’s Referral Service: 1300 766 491

If you or someone close to you is in distress or immediate danger, please call 000.

I don’t think I had any idea that anything that was happening was avoidable. I thought at that point that that’s just how it is, and that’s what life is like. I thought other people just coped with it better and I just wasn’t trying hard enough.

Hazel

Teen domestic violence and abuse

Domestic violence and abuse (DVA) is a national crisis impacting individuals, families and communities. In Australia, a large body of evidence informs our understanding of and responses to DVA amongst adults. There is also increasing awareness of adolescent violence in the home (AVITH) and the impacts of family violence on children as victims in their own right. Yet there remains a significant gap in acknowledging and understanding domestic violence and abuse experienced by young people under 18 within their own partner relationships.

Whilst State and Federal governments have increased their commitment to ending relationship violence and abuse, there is little if any recognition that this happens in teen relationships. Legislation does not clearly recognise children as victims of teen domestic violence and abuse in most jurisdictions in Australia. The focus of most policy and research related to teens and abuse is on witnessing parental/family violence or abuse toward a parent or other family member (AVITH).

Why we conducted this research

This research represents the first Tasmanian study of teen domestic violence and abuse, and one of few studies nationally.

The project was initiated in response to consultation with service providers across Tasmania who identified teen domestic violence and abuse as a prevalent and culturally embedded problem for young people aged under 18 years, and observed significant gaps in support services and legal responses in this state.

What is teen domestic violence and abuse?

For the purposes of this study, teen domestic violence and abuse is defined as:

A pattern of behaviours (actual or threatened), that may be physical, sexual, emotional or psychological in nature, that are used to gain power and maintain control over the current or former teen partner, and results in physical, social, emotional or psychological harm in those subjected to, or otherwise exposed to those behaviours.

Teen domestic violence differs from adolescent violence in the home (AVITH) which refers to family violence where a young person is abusive towards their parents or siblings.

Hopefully now I can help other people, so they don’t go down the same path, or get trapped in the same situation.

Ali

Who participated in the research?

For this research Anglicare interviewed 17 young people aged 18-25 who had experienced violence and abuse in their intimate partner relationships when they were under 18 years of age.

We also heard from 20 professionals in the housing, education, youth and welfare sectors who work with young people aged 12-17.

Key findings

The key characteristics of the 27 relationships described by young people were:

- Over half of the relationships started before participants were 16 years old.

- Almost all (25/27) involved a male-identifying abusive partner and female-identifying victim-survivor.

- Almost all were 6 months or more in duration.

- About one-third involved significant age gaps ranging from 8-22 years.

- About two-thirds of abusive partners were also under 18 when the relationship started.

- Almost half of the participants were in two or more abusive relationships.

Domestic violence and abuse is happening at an alarming rate in Tasmania

The findings from this research estimate that in the previous 12 months:

- up to 40% of Tasmanian teens aged 18/19 may have experienced domestic violence and abuse in their relationships

- young people (males and females combined) aged 18-19 in Tasmania were more likely to report experiencing domestic violence and abuse in their relationships when compared with their peers nationally (39.6% compared with 28.5%)

- Tasmanian females aged 18-19 were more likely to have experienced physical abuse in their relationships when compared with their peers nationally (29.2% compared with 11.8%)

- Tasmanian males aged 18-19 were more likely to have experienced sexual abuse in their relationships when compared with their peers nationally (14.9% compared with 4.3%).

“It felt like a web that I was trapped in”

The conditions that trap teens in violent and abusive relationships

Many teens are trapped in violent and abusive relationships. This research revealed some conditions outside the relationship strengthen the trap:

- a culture where violence and abuse is normalised

- a lack of safe, secure housing and other material resources

- a need for love and connection but limited experience or understanding of healthy relationships.

When violence and abuse is common, glorified and even condoned among peers, family and the community there is little opportunity for victim-survivors to question if their experience is abnormal.

Many of the participants were dependent on their abusive partners for housing. Earning little or no income, having inadequate access to Centrelink benefits, and with almost no access to affordable housing, these teens were in an invidious position. For many of them, leaving the relationship would have pushed them into homelessness.

With limited or no relationship experience, inadequate exposure to Respectful Relationships Education, and motivated by a natural desire for love and connection especially in the context of family breakdown and absent parents, these teens were frequently ill-equipped to navigate violence and abuse in their own relationships.

He started punching me in the gut… And his best mate stood there and watched him… I think he knew in a way I wasn’t in the wrong, but he wasn’t going to say something to his best mate, he wasn’t going to stick up for his best mate’s girlfriend. He’s going to stick up for his best mate.

Ali

I was so scared of being homeless again.

Hazel

I said, “Well, like, I have no family, I have no money. I’m at risk of homelessness;” and all they gave me was a Kids’ Helpline number… The system failed me… The only thing that they could do for me to get money is get Tom to claim Family Tax Benefits… Yeah, so I was fucked…They actually made it worse for me by giving him money to look after me and making him my guardian.

Katie

“I was a hit harder away from losing my life”

Young Tasmanians’ experiences of domestic violence and abuse

Participants described a number of tactics or behaviours that in their experience of domestic violence and abuse, broken into three categories relating to control of:

- what happens to your body

- your freedom and choices

- your thoughts and emotions.

Abusive partners often employed these strategies simultaneously or interchangeably, and these behaviours could change over time (usually escalating in severity).

Controlling what happens to your body

The stories of young people in Tasmania revealed that control and power over their bodies occurred through physical violence, alcohol and other drug use, and sexual violence and abuse.

One of the most disturbing findings from this study is the horrific levels of severe physical violence endured by participants. Several of the young people experienced life-threatening physical assaults, including the use of firearms, knives or other weapons; choking (a known risk factor for intimate partner homicide); shoving, hitting or biting; being forced to drink toxic substances, and being imprisoned. Many of these actions could have had potentially fatal outcomes. All of the victims experienced danger and fear, and most suffered serious physical injuries or were trapped in confined spaces.

Alcohol and other drugs exacerbated the severity of violence and were used to groom, sedate and sexually assault participants in abusive relationships.

Sexual violence and abuse was also a feature of many of the relationships described by young people. They described sexual violence and abuse that involved physical force, coercion, forced intoxication and other acts that served to degrade or humiliate them.

There was a night where he choked me to near death… I was lucky that he actually let me go when my face went blue.

Lily

He goes, “You want to run, because I’m going to fucking shoot you.” So I’m like, “What?” and he’s literally pulled it, let off a shot, so I’m like, “Fuck, oh my fucking God.”

Elise

I can still smell the alcohol on his breath. And he held me up against the wall. And I remember his mum screaming at him to let me go.

Saskia

I was pretty much raped the whole entire time I was living with him, because I never wanted to have sex, so he would just come home and force himself on me when I’m in bed.

Jess

Controlling your freedom and choices

The freedom and autonomy of participants was controlled by abusive partners who enforced explicit rules, micromanaged their behaviour, monitored their movements and actions (including through the use of technology), and isolated them from friends, family members, community, school and work. Some participants also experienced financial abuse.

At a life stage where contact with peers, school, family and work are critical, many of the young people who participated in this study were isolated and alone. Tactics included restricting contact with or causing conflict with friends and family, and monopolising the time victim-survivors had to develop or maintain other social and family relationships.

He made me tell him all my passwords, and then he changed all my passwords and put his mobile number on it so I couldn’t retrieve my accounts ever… Facebook, Snapchat, Instagram.

Katie

He just got real controlling, like I wasn’t allowed to have friends, I wasn’t allowed to see my family, I wasn’t allowed to leave my house without him knowing where I was going, or even if he knew where I was going, I wasn’t allowed to leave without him, he always had to be with me.

Ali

Controlling your thoughts and emotions

Abusive partners used four groups of behaviours to control how participants thought and felt:

- manipulation

- gaslighting

- eroding self-worth

- inciting fear through threats and intimidation.

Participants felt manipulated into thinking and acting in ways that benefited their abusive partner and disadvantaged themselves. Examples include victim-survivors taking blame for their partner’s criminal activity, withdrawing from education and training, and being groomed into entering a relationship with a much older man. As well, gaslighting techniques left many victim-survivors believing that they were to blame for the abuse they were experiencing.

Participants described a range of behaviours aimed at diminishing their self-worth. Shame-inducing behaviours included being called names, criticised, humiliated and degraded, both in private and in front of their friends or family. Perpetrators also used threats and intimidation, to incite fear and coerce compliance. Tactics included damage to personal property or homes, and threats of self-harm and suicide.

He would say, “You made me do this, Gina. If you had just listened to me, this wouldn’t have happened.”

Gina

He used to spit food on me and tell me I’m worthless and I’m nothing.

Elise

“I’ll never be the same”

The acute and chronic impacts of teen domestic violence and abuse

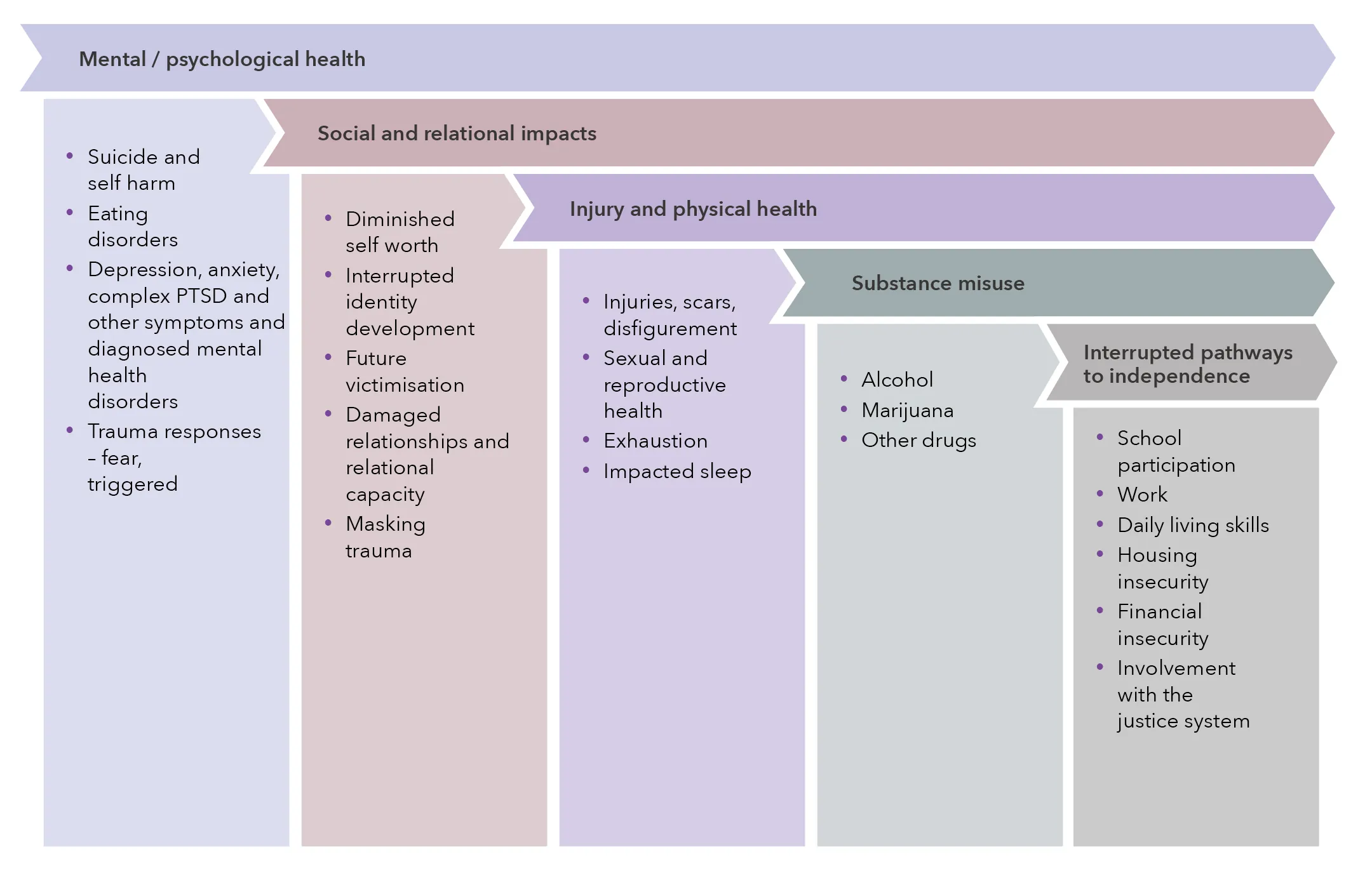

Teen domestic violence and abuse has profound and serious immediate and long-term impacts on victim-survivors. All participants live with daily emotional and psychological impacts reminding them of the violence and abuse they experienced, and some have painful or visible evidence of injuries inflicted by abusive partners. The cumulative detrimental impacts of teen domestic violence and abuse are evident in the emotional, psychological, social, developmental and physical effects described by participants in this study.

Interrupted identity development is a significant adverse outcome of teen domestic violence and abuse with potentially lifelong implications. How young people see and feel about themselves, learn to make choices independently, and establish meaningful connections with others is crucial as they explore their identity through the transition from childhood to adulthood.

The impacts of violence and abuse are not isolated, easily disentangled outcomes. They are intertwined with each other and not experienced in the same way by all young people. Some of these impacts may increase risk for ongoing victimisation and other health and wellbeing consequences later in life.

There’s not much to hang onto after they’ve broken you as a person… I’m always on the verge of tears. I just have this hole in my chest. It’s like someone’s physically punched me through the chest and I just – it feels heavy and empty at the same time. I don’t know how to explain it. It’s just my heart is broken physically.

Katie

It shapes you differently to who you thought you were.

Jess

It directly affected and impacted all the important things that you’re doing that age to set yourself up, your future life, your future career, your future rental history…

Elise

“It’s so hard to even ask for that help in the first place”

What we can do to prevent and respond to teen domestic violence and abuse

Responsibility for preventing and responding to this issue lies with adults, not children. The views of young people and professionals demonstrate some of the complexities in providing supports and interventions to young people and highlight barriers that need to be considered in planning and delivery. Whilst all participants described what could have helped them, a number stressed how hard it is to receive help once violence and abuse is entrenched in the relationship.

You can have as many helplines as you want. But until there’s physically someone there holding your hand, walking you out of there, a lot of people won’t get out. A lot of people will just get stuck because it’s so hard to even ask for that help in the first place.

Jamie

Education that empowers

Young people and professionals were clear that greater capacity, skills, knowledge and resources to develop and maintain safe, healthy and happy relationships were critically missing from the lives of young people. This education needs to be direct and up-front about teen domestic violence and abuse, build self-worth and be available to all teens.

Education about abusive relationships, what they are, what happens to people if they don’t leave, all of it. I wish I was actually taught in school the red flags… There needs to be a lot more education around it.

Saskia

Protection when in danger

Participants and professionals identified two main sources of protection:

Formal supports – for example the Child Safety Service, police, emergency housing. There was a shared view among workers that the formal supports available in Tasmania were either insufficient or were not employed to their full extent, arising from gaps in legislation, funding and service delivery.

Informal supports including friends, family members or strangers – for example intervening in incidents, calling the police or providing refuge. Informal supports were particularly important for teens when formal protective mechanisms were unavailable, inappropriate or not what they wanted.

They [Child Safety Services] don’t pick up our young people now, so why would they pick them up if they were in an unsafe relationship?… Child protection, to be brutally honest, for a 15-year-old… I’d be surprised if they’d step in there unless there was considerably younger siblings in the house.

Trish, worker

She would come if she would hear yelling or banging… she would bring tea, or just something to intervene.

Jamie

People who care about them

Young people need to know there are responsible, safe, trustworthy adults in their lives they can count on to raise concerns and offer support. Teens emphasised the need for people to believe them when they disclose a violent and abusive relationship, be persistent in condemning their partner’s violence and abuse, and offer them an alternative path to care and support.

My mum, my friends, anybody that sees it, like my teachers, anybody that can see the relationship with red flags. Anybody that is worried for me, I want them to tell me.

Addison

Access to housing and material resources

Few of the teens had economic resources, and this significantly constrained their ability to escape a violent or abusive relationship. Young people and professionals described feeling failed by systems that do not adequately provide teens with access to safe and suitable housing and material resources for escaping violence and abuse.

They are children at the end of the day. They… don’t have any other options sometimes… So, they go back.

Matilda, worker

Trauma-informed, specialist teen domestic violence and abuse services and trained professionals

This study found few services for teens experiencing or using violence and abuse in their relationships. Of those that do exist, awareness of and accessibility are limited. Tasmania needs:

- trauma-informed specialist support and programs for teen victim-survivors

- programs for young people using violence and abuse in their relationships

- a supported and highly trained workforce.

The lack of services, specialised services, for teenagers just puts them at such high risk of harm.

Heidi, worker

Recommendations

Teen domestic violence and abuse requires an immediate, systemic and multisectoral response.

The report recommends:

1. Review and, where appropriate, reform legislation to ensure children are protected from violence and abuse in their intimate partner relationships.

2. Address norms and values that normalise and/or condone violence and abuse.

3. Eliminate the choice between homelessness and violent and abusive relationships.

4. Provide parents and caregivers with targeted support to build positive relationships with their children and protect them from domestic violence and abuse.

5. Increase the financial independence of children impacted by domestic violence and abuse.

6. Provide specialist teen domestic violence and abuse supports and services supported by a sustainable workforce of teen domestic violence and abuse specialists.

7. Mandate the delivery of trauma-informed, evidence-based Respectful Relationships Education (RRE) that is co-designed with children and young people and begins when children enter the education system in all government, Independent and Catholic schools.